Funding Opportunities – Development Beyond Conflict

HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES

Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) in central Africa has, for years, been an arena in which human rights abuses have been perpetuated against the men, women and children who survive through the hard labor of extracting, transporting, processing and trading of minerals. The Dodd Frank Act and the OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains seek to remove such abuses from the sector and, to achieve this, iTSCi seeks to ensure that mines are free from the presence of armed groups and that human rights are respected.

WOMEN IN MINING

Women constitute a significant proportion of the mining sector across the Great Lakes Region (GLR) yet they face often significant discrimination and risk in many areas. They often receive low pay for their work. Very frequently women are excluded from any form of training and therefore end up relegated to menial and lower-paid tasks. Women are often expected to combine their work in mining with their household responsibilities leading to a very heavy work burden. This can also mean that women are obliged to bring their children to the mines which can be a starting point for child labour. Despite the fact that mechanisation should intuitively make it easier for women to work in mining as it reduces the physical strength needed, in fact the number of women in mining reduces with mechanisation due to discrimination against women receiving formal training and access to equipment. For this reason, a gender focus in ASM formalisation is essential to ensure the result is inclusive of women rather than causing further discrimination.

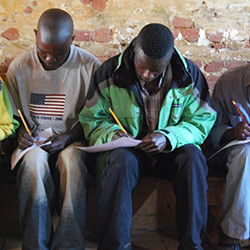

STRENGTHENING ORGANISATIONAL CAPACITY

Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) in the Great Lakes Region (GLR) often suffers from poor levels of organization, representation and institutional capacity. Artisanal miners are required to be organised into cooperatives however these often end up being business units or groups of traders with little actual representation of the miners themselves in any decision-making processes. These often differ from general concepts of cooperatives and may deliver only limited, if any, dividends and benefits for their members. Understanding of the legal requirements of cooperatives’ operations is often at a low level, as is capacity to take full advantage of business opportunities. In all countries of the GLR, miners themselves are generally poorly represented in forums and consultations and face challenges in exercising their rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining. Some miners’ associations exist to group miners together to give them a higher degree of visibility and representation but these need support to strengthen their activities.

CHILD LABOUR

The OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains recommends that companies sourcing from conflict-affected and high-risk areas should have strong policies in place including a model supply chain policy seeking to avoid the worst forms of child labor.

Child labour is a reality in some artisanal mines of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) where boys and girls aged perhaps from five years upward are engaged in an array of work in and around the mines from lower risk, supporting work to some instances of worst forms of labour involving actual mining and mineral processing. Children work in mines for a wide variety of reasons. They are driven into the mines by poverty and their work is an essential contribution to their families’ overall welfare. A complex array of drivers and factors which span social, cultural, economic, and pragmatic issues are intertwined around the phenomenon and require a sophisticated response.

HEALTH AND SAFETY

Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) mining involves the manual extraction of minerals using rudimentary tools and techniques. It is often carried out on an informal basis with little geological knowledge and scant attention paid to mine management or health and safety. ASM mines often present a wide range of physical hazards to workers which compromise their safety and wellbeing.

The health impacts of artisanal mining are not limited to the miners and the mines. Diversion and siltation of water sources affects all surrounding and downstream communities too. Also, due to the often migratory nature of artisanal mining, miners and mineral transporters can spread illness and disease, particularly if they engage in promiscuous sexual behavior. Child and youth labor is prevalent in many mines and these young people are particularly prone to physical and psychosocial damage.

PRODUCTIVITY AND EFFICIENCY

Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) is frequently inefficient in terms of its identification, exploitation, management, and processing of mineral resources. ASM is often carried out with little geological knowledge and prospection may be based on factors such as evidence of historical workings, chance discoveries of minerals, exploitation of abandoned industrial mines, rudimentary prospection, rumour and luck. Mines are often opened with poor understanding, if any, of the nature and presentation of the mineral body, its extent or value. Exploitation techniques are often very basic with inappropriate tools and methods being employed by unskilled workers. Mineral recovery and processing techniques may be inefficient resulting in wastage, and inadequate site and

waste management result in lost opportunities and doubling of effort as well as health and safety risks. Mines may be high-graded to remove the most accessible and most valuable minerals, leaving the rest behind and wasting the mine’s overall potential. Mines may be abandoned as near-surface minerals are exhausted despite their having further, significant production potential.

ECONOMIC STRENGTHENING

Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) is a hugely important livelihood for tens of thousands of people in the Great Lakes Region (GLR) who produce minerals by hand, using rudimentary tools, in remote sites. However, the potential for ASM to deliver long term value to the miners and surrounding communities is currently unfulfilled. Minerals deliver immediate value to miners when traded, however, all too frequently, the income from the transaction is used for short term needs rather than longer term development. Few miners know how to work efficiently to maximize mineral recovery, and few know the value of the minerals they produce in terms of grade and relative pricing. Furthermore, literacy and formal education levels are often low in ASM communities due to the migratory nature of the work, the remote location of the mines, and the frequency of child labor in ASM at the expense of school attendance. In the DRC, for example, over 30,000 artisanal miners produce minerals containing 3T minerals which enter into the iTSCi system. The majority of these miners, both men and women, have low levels of literacy and no opportunity to engage in adult learning. Many miners are in debt to informal creditors and sponsors who ‘pre-finance’ their work, often with resulting trade commitments and high levels of interest. Miners regularly cite lack of access to formal credit and financial services as being major obstacles to improving the efficiency of their activities. Yet few miners have the necessary credentials to make them attractive clients for financial services as they often lack security of tenure for their mine site, they may have no fixed address due to the migratory nature of their work, and financial services may simply not extend to remote mining areas. This is a situation which can be improved by self-generation of capital through savings, management of debt, and financial acumen.